I started the New Year in Harar, Ethiopia, where I was one of few who actually acknowledged the event. The day was like any other day for most Hararis. Ethiopian New Year falls on September 11 (September 12 in the leap year) so there were no fireworks in the sky the night before. It was quite surreal to wake up in a traditional Harari house in this historic walled city and think about the year that lay ahead.

Over the past month I visited two regions that can be considered “on the periphery” of their respective countries: the Harari region in Ethiopia, and the state of Goa in India. These regions are the smallest in Ethiopia and India, and are often characterized as being in their respective countries but not of their respective countries. It is this air of exceptionalism that attracted Victorian-era intellectuals like poet Arthur Rimbaud and explorer Richard Burton. Harar is the Muslim heart of Ethiopia, and Old Goa the Catholic heart of India. At the same time that they are portrayed as epicenters of great religious devotion, they are often branded as colorful, relaxed, fun, and “other:” a deviation from the norm, a place to break free from the usual.

Figure 1. Arthur Rimbaud Cultural Center in Harar, Ethiopia. An Indian merchant built the current edifice, now over 100 years old.

Figure 1. Arthur Rimbaud Cultural Center in Harar, Ethiopia. An Indian merchant built the current edifice, now over 100 years old.

These were trade cities – Harar thrived because of its strategic location along trade routes connecting landlocked Ethiopia to the port city of Zeila in Somalia, the Gulf of Aden, and the Arabian Peninsula.1 Part of the reason I chose to visit Harar was its trade relationship with India. I believed it would be a nice transition between the two countries. Old Goa, a prosperous port under the Islamic Adil Shahi dynasty, fell to the Portuguese in the sixteenth century. Since these were cities with far-reaching cultural and economic contacts they are often defined by their architectural pluralism. Their positions on the periphery, however, often paint them as “exceptional” which is problematic if one is attempting to understand them within the larger context of cultural heritage and preservation studies. As architectural historian Preeti Chopra emphasizes, “Far for being pure, most cultures are a product of diverse influences from others, a result of trade, travel, and conquest.”2

Figure 2. Church of St. Cajetan (1655), Old Goa, India.

These regions were contested grounds, important strategically for various empires, dynasties, and religious orders. Trade influenced the development, urban character, and architecture of both the Harari region and the state of Goa. The resulting architectural heritage, then, often highlights structures that facilitate trade such as fortifications, administrative buildings where transactions occurred, and the resultant residential areas and educational and religious facilities that reflect the splendor and magnificence of the trade economy in these areas.

Harar the Walled City

If one chooses to visit Harar by air, one must fly into Dire Dawa. Harar and Dire Dawa (formerly Addis Harar) are located in eastern Ethiopia. I spent a week in Dire Dawa, a city established at the turn of the twentieth century that owes its development to the railroad. Although the city acted as an important node from Djibouti to Addis Ababa, the portion of the rail network running from Dire Dawa to Addis Ababa is now defunct.

The Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Franco-Éthiopien took over railway operations in 1908 after the Imperial Railway of Ethiopia, founded in 1894, folded under financial troubles. The Dire Dawa railroad station is the key architectural edifice associated with the city, and its construction had significant impact on the city’s planning. There is scant literature written about the urban development and architectural heritage of Dire Dawa, and most travel guides treat it as a place one should only visit in transit to Harar.

Figure 3. Google Map depicting the two major sections of Dire Dawa: Kezira and Megala.

I found the layout of the city to be quite intriguing. In Dire Dawa there is a stark contrast between the European Kezira section or “new town,” and the older Islamic section, Megala. In Kezira one finds airy restaurants such as Chemin de Fer, housed in a building constructed in 1912, tree-lined streets, shaded villas, and grand boulevards that converge on the railroad station. In Megala one finds a more organic growth pattern, narrower streets, winding roads, and cul-de-sacs. The presence of Indian and Arab traders in Dire Dawa influenced the design details of buildings in both sections of the city.

Figure 4. Commercial building in Megala, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.

Figure 4. Commercial building in Megala, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.

Figure 5. Residential buildings in Megala, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.

Figure 5. Residential buildings in Megala, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia.

The jugol city of Harar is considered the architectural prize of eastern Ethiopia, and it also stands as the heart of Muslim Ethiopia. Muslim Ethiopians consider Harar to be the fourth holiest city in Islam, after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.3 There are an estimated 90 mosques and many Quranic schools within the 48 hectares enclosed by the city walls. Harar was founded in the eighth century, Sheikh Abadir introduced Islam in the twelfth century, Emir Nur built the city walls in the mid-sixteenth century, and the city was an independent emirate from 1647 to 1875. The Egyptians occupied the city from 1875 to 1885, Menelik II conquered it in 1887, and the Italians occupied it from 1938 to 1942. Each phase of governance is reflected through the remaining cultural heritage within and outside the city walls.

Figure 6. Mosque built during Egyptian occupation of Harar.

Figure 6. Mosque built during Egyptian occupation of Harar.

For much of its history the city was closed to non-Muslims, and it was only after Egyptian occupation did the city become more accessible to opportunistic foreign traders and merchants. Today coffee and khat are two of Harar’s primary exports, and while those industries are still important to the lifeline of the city; increased tourism is also a welcome addition to the economic structure. UNESCO recognized Harar as a laureate city in its short-lived Cities for Peace Prize in 2002-2003 and inscribed the walled city on the World Heritage List in 2006.4

Figure 7. Gidir Magala. Italians built this market structure during occupation of Harar.

Figure 7. Gidir Magala. Italians built this market structure during occupation of Harar.

The walled portion of Harar retains much of its urban fabric. When Amir Nur erected the walls in 1567 there were five gates through which visitors to the city had to pass (today there are six). These gates have become a distinguishing architectural feature of the city, and are even imprinted on the bottles of the locally produced Harar beer.

Figure 8. Courtyard of house with elaborate detailing near the Sheik Abudir mosque, Suqutat Bari area.

Figure 8. Courtyard of house with elaborate detailing near the Sheik Abudir mosque, Suqutat Bari area.

The most celebrated aspect of Harari architectural heritage is the traditional Harari house. I chose to stay in one of the popular guesthouses to get a feel for the everyday use of the structure. The programmatic layout of the house is highly prescribed, following cultural conventions. Women and men have certain spaces dedicated to their use, all with various layers of privacy. There are numerous levels to the seating in the living room (gidir gār) that denote the status of family members and guests. Basketry is a prime decorative ornament for the interior of the houses.

Figure 9. Interior of model house at the Harari National Cultural Center.

Figure 9. Interior of model house at the Harari National Cultural Center.

Modern Harar extends to the west outside the city walls. While it was certainly not my intent to highlight architecture of the Italian occupation in all of my blogs on Ethiopia, I find it necessary to mention here. Whenever I made my treks outside the walled city to document architecture from the twentieth century, people were surprised, curious, and a bit baffled as to my intentions. The heritage of significance, according to the guides, townspeople, and tourists I spoke to, was to be found within the walls. Serge Santelli’s chapter “The Structure of the City,” in Harar: A Muslim City of Ethiopia was most useful to me in this regard, as he treats both the old and new city as what they are—two sides to the same coin. That chapter helped me overcome the disconnect I felt when trying to piece the city together myself. It is true, the richness of traditional Harari culture is concentrated within the walls of the old city, and that should be admired. This should not happen, however, to the detriment and disregard for the rest of the city itself.

Figure 10. Former Italian municipio in newer portion of Harar, outside city walls.

Figure 10. Former Italian municipio in newer portion of Harar, outside city walls.

Goa: Rome of the East, Pearl of the Orient

I do not believe Goa to be the Rome of the East. Perhaps in a religious sense it is a useful analogy, if one desires to think about Old Goa as a powerful concentration of Catholic practice. Perhaps. But trying to reconcile the nickname with the reality feels false for two reasons. The first is that Rome, the “Eternal City” is truly incomparable. The second is that Old Goa never reached the complexity in function, design, or development that Rome did. Part of the colonizing project, however, is to recreate the familiar in foreign lands, and to engage in heavy boosterism to spread propaganda for political and economic reasons. All that being said, Goa is a gem. An absolute treasure.

I spent half of my time in Goa in Panaji (Panjim). It is the capital of the state of Goa. I was surprised to learn that the Portuguese had control of the area until 1961. The second thing that surprised me was the discovery that, along with a distinct architectural style that made a lasting imprint on the region, the Portuguese brought the marigold to India. The practice of Catholicism and the architecture it produces felt very much imported, but the marigold has been thoroughly integrated into the social, religious, cultural, and political customs of India. Hindu, Buddhist, and Catholic shrines are all embellished with marigolds. Marigolds are draped on the shoulders of important figures memorialized as statues. The marigold is a ubiquitous symbol of India.

Panaji was colorful – a distinction also held by the city of Harar. The main advertised attractions of the city were the Church of the Immaculate Conception and the Goa State Museum. The museum was a gloomy affair – its modernist and geometrical design hinted at the grand intentions behind its erection. The building maintenance and the lackluster curatorial effort, however, belied a slim budget that held the operation back from its potential.

Figure 11. Commercial building in São Tomé neighborhood of Panaji.

Figure 11. Commercial building in São Tomé neighborhood of Panaji.

It was the vernacular architecture of Panaji that stood out the most. I stayed in the Old Quarter, or Fontainhas. This was one of the Portuguese residential quarters, and heritage tourism was gaining a foothold in the area. Boutique accommodations catered to a range of economic situations, and several art galleries displayed a variety of work—from traditional ceramic designs to contemporary Goan expressions.

While doing research on the region I came across a curious passage in an article about the contested heritage of Goa. Travel writer David Tomory covered the protests against the 1998 quincentenary celebration of Vasco da Gama’s landing in India. Tomory states:

The beauty of heritage—or the privately run heritage business—is that it doesn't depend on the past, offering only history without tragedy—the simple recreation of history's fun bits, such as food, costume, music and “ambience.” Heritage is the old romantic stuff that nobody minds. You can't see it being as contentious in Goa as “history” can be, but you never know…5

This passage made me think about the tricky relationship between heritage and tourism and the ability for those who have an appreciation for both heritage and history to gloss over controversy for the sake of tourism. I am writing about the beauty of Fountainhas, but I am not writing about the Goa Inquisition. I delight at the beauty of architectural syncretism as it is manifest in Goa. I wonder what the Hindu-practicing Goans think about this heritage. When I visited the Goa State Museum I cringed at the images of Goans carrying Portuguese men from one place to the next on palanquins. The beauty of the architecture comes at a price—one of religious oppression and cultural subjugation.

Figure 12. St. Francis of Assisi (1661), Old Goa.

Figure 12. St. Francis of Assisi (1661), Old Goa.

With those factors in mind, it must be said that the churches and convents of Old Goa are truly exceptional. The crisp white structures stand as strong contrasts to the ultramarine sky. The heavy concentration of religious structures at once reminded me of Antigua, Guatemala, another abandoned capital of a colonial territory.6 I visited Old Goa on a Sunday, Se Cathedral and the Basilica of Bom Jesus had active church services. Tourists (and there were many) were not allowed into the sanctuaries during that time, but they could stand to the side of the entrance and take pictures. The Basilica of Bom Jesus additionally allowed tourists to take a side entrance to visit the relics of St. Francis Xavier, the Jesuit leader entombed in the building. Circulation continued from the tomb to the cloister where a Christmas display was still exhibited, and an art gallery highlighted the work of various artists. This setup made me think of some of the major pilgrimage churches I taught about in class, and how they worked as both sites of visitation and sites of worship.

Figure 13. Detailed woodwork embellishing the St. Francis Xavier tomb niche. Scholars have highlighted the masterful dexterity of Indian carvers who worked on the churches in Goa, albeit in a Portuguese Baroque style.

Figure 13. Detailed woodwork embellishing the St. Francis Xavier tomb niche. Scholars have highlighted the masterful dexterity of Indian carvers who worked on the churches in Goa, albeit in a Portuguese Baroque style.

Circulation was an important component of a church’s functionality, one that was often overlooked in art historical texts that focused on paintings and sculpture. I wondered how people related to each other in pilgrimage spaces—were they rushed through and hissed at, as I was at the Basilica of Bom Jesus? Was it always the crowded spectacle I experienced on that Sunday in January? I had, up until my time in Ethiopia and now in India, a very romantic idea of religious pilgrimage—a journey of solitude and quiet reflection. I participated in a great pilgrimage while in Harar, traveling to Kulubi for the feast St. Gabriel. The sea of bodies pressed together, the noise, and the vendors reminded me of my time in a crowd of thousands at the first Obama inauguration. My experience at the Basilica of Bom Jesus, being funneled through passageways for a quick glimpse of St. Francis Xavier’s tomb was reminiscent of my trip to the Louvre and the half-second I spent in front of the Mona Lisa. I have begun to think that the chaos of pilgrimage sites is but a small fraction of what makes the experience exciting for the pilgrims/tourists.

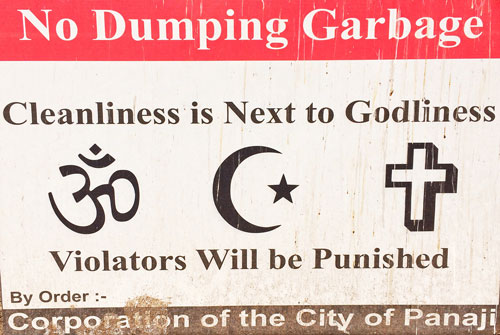

The big story on the news this morning was President Obama proclaiming that Gandhi would be disappointed in the religious intolerance of contemporary India. I have been in India for less than a month, and I am not an expert on the religious or political situation, but that certainly was the opposite of my impression of the country. While in Panaji I came across a governmental sign discouraging city residents from dumping garbage. It stated, “Cleanliness is Next to Godliness” and displayed religious icons of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity. It was in Panaji, the capital of the Catholic state of Goa, where I visited two active Hindu temples. The imposition of Catholicism on the region did not snuff out other religious practices.

Figure 14. Cleanliness is Next to Godliness.

Figure 14. Cleanliness is Next to Godliness.

Figure 15. Temple in Panaji. I was unable to ascertain the name of this structure.

Harar and Goa offer very important lessons about our assumptions of architecture on the periphery. These two areas are “othered” in the critical discourse of their respective countries, but are in fact central to their respective religious communities. Harar and Goa are at once on the edge and in the center. Architectural, cultural, and religious syncretism can be found in these places, and in other cities around the world that have served as major nodes for commodity trading. These cities are not an exception – they are the result of trade, travel, and conquest.

H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship Google Map

Recommended Readings

Paul Axelrod and Michelle A. Fuerch, “Flight of the Deities: Hindu Resistance in Portuguese Goa,” Modern Asian Studies 30 no. 2 (May 1996): 387-421

Carlos de Azevedo, “The Churches of Goa,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 15 no. 3 (October 1956): 3-6

Avishai Ben-Dror, “Arthur Rimbaud in Harär: Images, Reality, Memory,” Northeast African Studies 14 no. 2 (2014): 159-182

John F. Butler, “Nineteen Centuries of Christian Missionary Architecture,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 21 no. 1 (March 1962): 3-17

William Connery, “Within the Walls,” World & I 15 no. 12 (December 2000): 184-191

François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar and Bertrand Hirsch, “Muslim Historical Spaces in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa: A Reassessment,” Northeast African Studies 11 no. 1 (2010): 25-53

“Goan Residences,” Architecture + Design 17 no. 4 (July/August 2000): 76-84

Elisabeth-Dorothea Hecht, “The City of Harar and the Traditional Harar House,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 15 (August 1982): 57-78

T. P. Issar, Goa Dourada: The Indo-Portuguese Bouquet (Bangalore: Issar, 1997)

Rumi Okazaki and Riichi Miyake, “A Study on the Living Environment of Harar Jugol, Ethiopia,” Journal of Architectural Planning 77 no. 674 (April 2012): 951-957

Philippe Revault and Serge Santelli (eds.), Harar: A Muslim City of Ethiopia (Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 2004)

Isaac Sequeira, “The Carnival in Goa,” Journal of Popular Culture 20 no. 2 (Fall 1986): 167-173

Tibebeselassie Tigabu, “Dire Dawa's Good Old Days,” Africa News Service November 24, 2014

David Tomory “Reluctant Heritage,” Index on Censorship 1 1999 67-68

David Wilson, “Paradoxes of Tourism in Goa,” Annals of Tourism Research 24 no. 1 (1997): 52-75

1. See Richard Pankhurst, “The Trade of Central Ethiopia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 2 no. 2 (July 1964): 41-91 and “The Trade of the Gulf of Aden Ports of Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 3 no. 1 (January 1965): 36-81.

2. Preeti Chopra, “Refiguring the Colonial City: Recovering the Role of Local Inhabitants in the Construction of Colonial Bombay, 1854-1918,” Buildings & Landscapes 14 (Fall 2007): 124.

3. This title is disputed, as Kairouanin, Tunisia is also held to be the fourth holiest city of Islam. See John Anthony, “The Fourth Holy City,” Saudi Aramco World 18 no. 1 (January/February 1967)

4. See Jan Bender Shetler and Dawit Yehualashet, “Building a ‘City of Peace’ through Intercommunal Association: Muslim-Christian Relations in Harar, Ethiopia, 1887-2009,” Journal of Religion, Conflict, and Peace 4 no. 1 (Fall 2010)

5. Tomory, 68.

6. A series of plagues forced the abandonment of Old Goa for Panaji. Constant, deadly, and destructive seismic activity in Antigua forced abandonment of that capital.