Danielle S. Willkens is the 2015 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

In December, I travelled more than 2,000 miles around Cuba, exploring portions of the nation's central and southern provinces. My travels included a total of nearly two days on Viazul buses, ferry rides, day trips in a range of classic cars (with a handful of detours due to overheating engines), and an inter-Cuba flight where the use of any electronics or headphones were prohibited. In January, I will add another 1,000 miles to my odometer with trips to sites in the west and along the southern coast of the island. Therefore, the blog post at the end of this month will contain information about Cuba outside of the capital. Referencing many of the island’s diverse museums, nature preserves, tourist-centric sites, as well as places that typically escape the radar of travelers, the next post will feature the following cities: Camagüey, Cienfuegos, Holguín, Pinar del Río, Santiago de Cuba, Trinidad, and Viñales. In addition to containing UNESCO World Heritage sites, Cuba’s only architectural museum, and a few natural wonders, my travels around Cuba, thus far, have provided a different perspective on both Havana and the la lucha, the ‘battle’ for supplies and services that Cubans navigate on a daily basis. Despite these struggles as well as the overall tonal shift felt on the island following Fidel’s death and the state-imposed nine-day mourning period, the capital and other cities seem to have a renewed sense of patriotism: temporary, large scale images of Fidel cover buildings in the Plaza de la Revolution and an overwhelming number of Cuban flags appear across buildings of all shapes, sizes, and conditions (Figures 1–3).

Figures 1–3. Although many of the posters and flags that once adorned buildings in early December are now gone, there are several new murals underway in the capital and other cities. As per Fidel’s request, these murals don’t exclusively feature the Revolutionary leader but, instead, the tenants of the movement and other national leaders.

A Changing of the Guard

Unlike the Colón cemetery in Havana, filled with an array of large mausoleums of diverse styles, including experimental examples of modernism, the Cementerio de Santa Ifigenia (b. 1868) in Santiago de Cuba is largely composed of raised tombs in the neoclassical and eclectic styles (Figure 4). Modern monuments to the lost heroes of the nation exist outside of the cemetery walls, such as the massive sculpture to General Antonio Maceo (1991) in the Plaza de la Revolución and the marble, rationalist construction known as the Bosque de los Héroes (1973).

Figure 4. The entry allée of the cemetery is lined in terrazzo and framed by palms, banyans, and the surrounding mountains.

After a ceremonial trip through the nation, retracing the route of the Revolution, Fidel’s ashes were interred in a simple monument on December 4, 2016. With only a simple bronze plaque with the name ‘FIDEL’, the tomb sits in stark contrast to the adjacent mausoleum for national hero José Martí (1853–1895) (Figures 5 and 6). This bold, Art Deco mausoleum (b.1951) dominates the skyline of the gridded cemetery complex. The hexagonal structure features allegorical caryatids, referencing the original six provinces of the nation: Pinar del Rio, Havana, Matanzas, Las Villas, Camaguey, and Oriente (Figure 7).

Figure 5. The crenulated mausoleum for José Martí is the most dominate form in the complex.

Figure 6. Fidel’s austere tomb sits in front of a semi-circular columbarium for the revolutionary figures that fell during the failed siege of the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953.

Figure 7. With a lyre and a parchment, this caryatid represents the creative province of Matanzas and in the figure’s shield is the Castile of San Severino.

Inside, a Carrara marble statue of Marti sits below an intricate series of geometric skylights and somberly overlooks an urn draped in Cuban flag (Figures 8 and 9).1 Commissioned as the winners of an open architectural competition held in 1946, known as the Concurso Inter-Americano, the building’s design and sculptural detailing were executed by Jaime Benavent and Mario Santí. In portions of the competition brief, posted online by a Cuban newspaper, the organizers stated that the mausoleum was intended to be a ‘tomb worthy of the Apostle Marti’ and with the common sighting of busts of Martí in gardens and on terraces throughout Cuba, a trip to his tomb in Santiago de Cuba can be seen as a patriot pilgrimage for many Cubans.

Figure 8. The stained glass of the clerestory and fossil-infused limestone give the tomb a warm color in contrast to the cool marbles and green landscape of the surrounding area.

Figure 9. Although designated as the writer’s final resting place and mausoleum after six re-interments, Martí’s ashes were lost in the early twentieth century and the story of his ever-moving mausoleums can be found in a portion of Rodríguez-Luis’s Re-Reading José Martí, 65–78.

In addition to its visual dominance in the cemetery’s landscape, the tomb was the central focal point for the changing of the guard ceremony that halts the cemetery’s visitors every half hour, drawing their attention to the mausoleum and the national anthem playing loudly over the cemetery’s speakers. Originally, three soldiers marched to Martí’s mausoleum as part of the ceremony, pausing for tolling bells to commemorate those lost during the nation’s struggle for independence in the 19th and 20th centuries before relieving the three soldiers keeping watch in the mausoleum. However, since December 4, this ceremony has been altered to include an additional soldier: one to keep watch over Fidel’s tomb (Video 1).

Video 1. This video captures the changing of the guard, a ceremony that occurs every half hour at the cemetery. The unsteady shots were due, in part, to constant jostling from the large number of people crowded behind the viewing gate.

Beyond the Vines at the Instituto Superior de Arte

In addition to witnessing changes around the island related to Fidel’s passing, in the beginning of December, I had the pleasure of traveling in Havana with the Soane's Foundation on their twelfth people-to-people trip to Cuba, liaising with the Design Leadership Network’s annual international trip. With a wealth of contacts in the city's architectural and artistic communities, four days with the Soane Foundation and their local guides provided access to a number of incredible sites such as a Neutra treasure that serves as the residence of the Swiss Ambassador (Figures 10–13), several of the structures related to the Bacardi family (Figure 14), a pre-Revolutionary mansion converted into the Museo Artes Decorativas (Figure 15), and the very newly restored headquarters of the Alliance Française (Figure 16).

Figures 10–13. The Alfred de Schulthess Residence was designed by Richard Neutra in 1956 in an exclusive, gated community west of Central Havana. The Swiss banker, his wife, and their three daughters occupied the home for only four years before it was transferred to Switzerland to serve as the residence of the Swiss Ambassador, who was also responsible for American diplomatic relations in Cuba between the time of the Revolution and the historic restoration of diplomatic ties in December 2014. Despite its distinction as the only home executed by the architect in the tropics, the project has many of Neutra’s signature design features such as the ‘spider-leg’ entry colonnade, deep eaves, beams that slip through impossibly large glass panels, and a highly reflective material palette including a pool that mirrors a longitudinal elevation that faces a landscape designed by Roberto Burle Marx. The home received a gold Medal from the Cuban National Association of Architects in 1958 and through careful preservation and restoration; the home retains many of the original design features including built-in and period furniture.

Figure 14. The Bacardi Building (1930) was restored in 2001. With ornate Art Deco details, including glazed terracotta, mosaics, and an iconic bat atop the finial of the tower, the building is highly recognizable in the Havana skyline and was one of the city’s first skyscrapers.

Figure 15. The Decorative Arts Museum in Vedado represents the scale and opulence of some of the residence in pre-Revolutionary Havana. Designed by Pariasian architects in 1925, the neoclassical residence was home to the Countess of Revilla de Camargo, María Luisa Gómes-Mena. Although the home is well preserved and restored, much of the gardens, are in disorder. In their prime, these phenomenal outdoor rooms were designed for large events, music performances, and to bring the entertainments of interior spaces out-of-doors.

Figure 16. Now the headquarters of the Alliance Française, the Casa de Jose Miguel Gomez on the Prado was built in 1915 and served as the home of Cuba’s second president, José Miguel Gómez.

As part of my trip with the Soane Foundation, we visited the Instituto Superior de Art (ISA), once known as the Cuban Schools of the Arts. This project was one of the first [and only], experimental architectural projects sponsored by the early revolutionary government.

As mentioned in last month’s post, no book can better illustrate the roots, scope, and history of the Schools of the Arts better than Loomis’s Revolution of Forms.2 Additionally, the documentary Unfinished Spaces brings the story of the schools to life through incredible interviews with the architects, former students, and even critics who contributed to the initial construction of the schools in July 1965.3 One evening after studio during my first semester of teaching at Auburn, I watched the documentary in rapt wonder: it was an extremely well-selected feature within the AIAS-sponsored film series and as I sat entranced by the story, and tragedy, of the schools, I had no idea that two years later I would have the amazing privilege to walk through these architecturally sacred spaces.

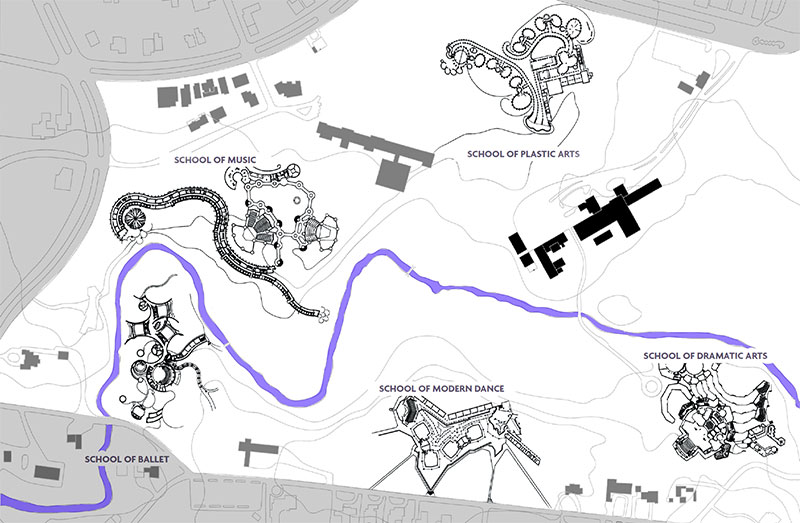

Today, a number of tour groups with artistic and architectural interests make visits to ISA but, like Loomis reminisced in reference to his first visit in the acknowledgements of Revolution of Forms, these groups only see one-fifth of the complex: the School of Plastic Arts (Plan 1).

Plan 1. This plan shows the original boundary of the Schools of the Arts, the location of the original clubhouse for the country club (solid black) that now serves as the administrative center for ISA and the location of the five subject-specific complexes, once connected across the hilly landscape by a series of bridges over the now very polluted stream. The author edited this image over a base plan of the complex from Loomis, John A. "Cuban Art Schools." ICON (2002–2003): 28.

In addition to being the most complete and well maintained of schools, The School of Plastic Arts is within easy access to the entry gate and the main administration building, once home to the clubhouse of the country club (Figure 17). The clubhouse also serves as an evocative place to introduce visitors to the story of the art schools. In addition to providing access to housing and raising literacy rates, the early tenants of the Revolution championed the arts. Therefore, it was highly symbolic of the new, socialist agenda that a privileged site, such as a golf course, was transformed into a resource that could benefit a larger portion of the population. However, before construction broke ground for the new Schools of the Arts, Che and Fidel played a round of golf at the seized country club.

Figure 17. As a headquarters of ISA, the clubhouse is full of activity, including musical performance exercises, impromptu dancing, and the occasional tour group.

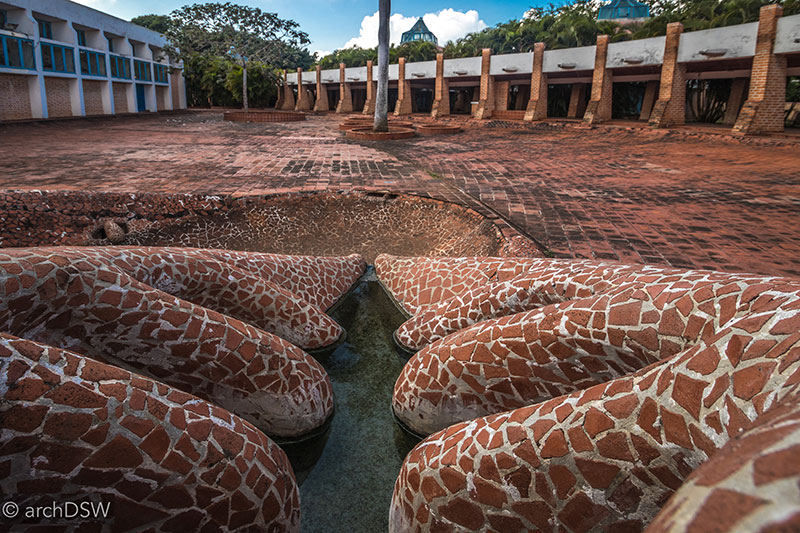

Cuban architect Ricardo Porro (1925–2014) was specifically selected for the commission and with the daunting task of designing five schools in a sloping, forested landscape, he enlisted the help of two architectural peers he met in Venezuela, Italian architects Roberto Gottardi (b. 1927) and Vittorio Garatti (b. 1927). Together, they worked with students to design and build some of the most striking examples of architectural resourcefulness: with the American embargo, steel was scarce for beams or rebar so the team turned to the use of locally available materials. A palette of brick and terracotta unified the projects and each architect employed variations of a Catalan vault system, with the direction of master mason Gumersindo, who learned the trade from his father’s work with Antonio Gaudí in Barcelona.

Rather than attempting to provide a comprehensive history of the schools, or dense narrative, the last section of this blog post will serve as a photographic essay on the current state of the schools. The second edition of Loomis’s book was published in 2011 and this also marked the year Unfinished Spaces wrapped post-production. Although both sources referenced the attempt to revive the construction and restoration of the schools that gained momentum in 2008, the subsequent world economic crisis and two hurricanes ceased much of these efforts. Today, Porro’s School of the Plastic Arts conducts classes, has active studios, and, on certain days, serves as a gallery for visitors (Figures 18–26). After meeting with a few representatives from ISA, I was able to visit other portions of the complex, exploring the current state of the structures. Porro’s other project, the School of Modern Dance, was the subject of the most recent renovation efforts but it receives only occasional use so mildew is beginning to take hold, once again, and palm debris litters portions of the site (Figures 27–31).

Thus far, I was unable to tour Garatti’s only project, the School of Dramatic Arts, but I know from discussions with ISA representatives that the School is in similar condition to Gottardi’s School of Ballet (Figures 32–56) and the School of Music (Figure 57–62). These sites resemble something from the History Channel’s series Life After People: nature is quickly taking over, with algae stains covering the northern walls of the brick complexes, bamboo invading corridors, and ivy crawling over the crumbling vaults that are delaminating due to the constant cycles of tropical downpours and intense sun native to the Cuban climate. In addition to the climatic stresses, these structures have also been subject to periods of surreptitious domestication: interior walls and domes bear the charred scars of cobbled kitchen fires when families occupied schools during Cuba’s ‘Special Period’ [a completely sarcastic term for the dire conditions in the nation in the early 1990s]. Today, graffiti and litter can be found throughout the School of Ballet and School of Music, but the surrounding landscape of the School of Ballet has been fairly well maintained, trimming the wild growth and tall grass featured in many of the photographs by Loomis and wide angle shots of Unfinished Spaces. At the School of Ballet and the School of Music, earthen floors cover the majority of the complexes, weathered bricks support the layered walls, and light streams through unglazed apertures. Especially in the corridors and beneath the vaults of the School of Ballet, it feels like one is walking through an ancient ruin, discovering forgotten paths and incredible, abandoned rooms. Of the thousands of photographs captured, the following few hopefully capture the spirit of the undeniable architectural innovation found within the sacred grounds of the Schools of the Arts.

Figures 18–26. The School of Plastic Arts contains classrooms, workshops, and studios related to drawing, painting, printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics. With narrow corridors that lead to a central plaza, the arrangement has been compared to a village and throughout the complex there are allusions to an Afro-Cuban goddess of fertility, Porro’s reference to the ‘birth’ of artistic inspiration.

Figures 27–31. Although dominated by more concrete in its material palette, the School of Modern Dance has clear visual and spatial connections to Porro’s work at the School of Plastic Arts. The plan’s formation evoked a shattered plane, referencing the simultaneous feelings of excitement and foreboding during the early years of the Revolution.

Figures 32–34. These panoramic views of the School of Ballet show the expansiveness of the project and its placement within a ravine of the former country club.

Figures 35 and 36. Much like the stream that runs through the former country club, separating the five schools, a sinuous path for collected rainwater runs through the School of Ballet.

Figure 37. The School of Ballet was approximately 90% completed when it was abandoned in 1965. For a period of time, the main performance hall was used for a circus school and various movies and television shows used the complex as a post-apocalyptic set. Over the years, these uses and looting have compromised aspects of the site.

Figures 38–39. The massive span achieved by the top lit dome of the main performance hall creates an impressive space with astounding acoustic resonance.

Figures 40–44. Throughout the School of Ballet, carefully placed apertures frame views of the complex. In select practice and dressing rooms, an oculus with a concrete screen provides the main source of natural light.

Figures 45–47. The ribbed elements of the dome, met by a concrete compression ring, and the vaults marking the primary axis of circulation are richly patterned with delicately twisting layers of brick and terracotta tiles.

Figures 48–50. These images show the corridor of the School of Ballet that acts as a spine, connecting the classroom spaces. Here, built-in seats provided students fixed places to watch instructors as well as framed views of the large practice and performance spaces.

Figures 51 and 52. Stairs leading from the classroom ‘spine’ to the upper level of the School of Ballet allowed students to walk atop their classrooms and peer through the pipe-like concrete protrusions that illuminated the classrooms and corridors below. Walking further along this grassy roofscape, one can actually step onto the top of the Catalan vaults of the complex.

Figures 53–55. These detailed views illustrate the declining state of the domes’ structural and material integrity at the School of Ballet. Without the protection of the terra cotta tiles, water is now invading the bonding grout and this may significantly damage the laminations as well as the connection points for tension rods that are supporting the vaults throughout the complex.

Figure 56. A view of one of the many ruined bridges; this one once connected a path between the School of Ballet and the School of Music.

Figures 57–62. Between the steep, eroding slopes, the rising water of the stream, and landscape debris, much of the School of Music was impassible. Nonetheless, certain practice rooms offered picturesque, framed views of the surrounding landscape as well as glimpses of the domes of the School of Ballet.