Aymar Mariño-Maza is the 2018 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Figure 1: Hien Luong Bridge, known as The Freedom Bridge

“Welcome to North Vietnam,” he said. Vu Van, our trusty historian and tour guide, pointed to his right over the bridge we were crossing to another, smaller bridge. “That is the Freedom Bridge.”

The unintimidating structure spanning the short distance across the Bến Hải River hid its significance well under its weathered paint—half baby blue, half Easter yellow. But I already knew that Hiền Lương Bridge had a long and troubled story to tell. Located along the 17th parallel, this bridge served as a strategic point between the North and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War (also known as the Second Indochina War, the American War, or the Resistance War Against America). It was built by the French, destroyed by the Viet Minh in 1945, rebuilt by the Vietnamese in 1957, used as a strategic transport passage by the Viet Cong, and then repeatedly targeted by the Americans in the infamous Operation Rolling Thunder. All this until it became less of a strategic point of interest than a symbolic one.

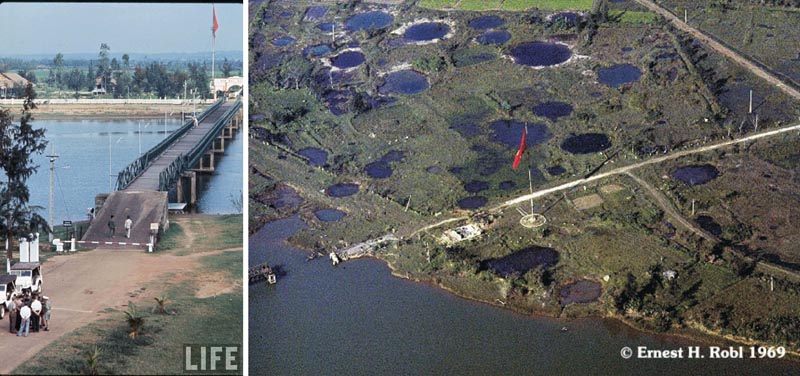

Figure 2: Freedom Bridge as seen during time of peace (left); Aerial of Freedom Bridge and land North of the Ben Hai River taken after the bridge was blown up (right)

Another similarly strategic-to-symbolic bridge is the Thanh Hóa Bridge, located some 400 kilometers north of where we stand. Also known as the Dragon’s Jaw (for its uncanny resemblance to the open mouth of that mythical creature), it crosses the Song Ma River.

The indestructibility of both these bridges has made them symbols of Vietnamese reunification. Every time either bridge was bombed by U.S. missiles, it was rebuilt by North Vietnamese hands. As one U.S. writer and retired Air Force colonel wrote about the Dragon’s Jaw, “after seven years, 871 sorties, tremendous expenditure in lives, 11 lost aircraft, and a bewildering array of expended munitions, the Dragon’s Jaw was finally broken.”1 But of course, it has since been rebuilt—though the writer failed to mention that at the end of his article.

We parked the car along the edge of the road and stepped out. The flat landscape around us did little to shield us from the harsh midday sun that came down through the cloudless sky. We were caught between the hot and rainy seasons, so that we had to trade our raincoats for sunglasses every few hours.

Figure 3: Aerial of the DMZ north of the Ben Hai River taken during the war

We looked out over the Bến Hải River. As Vu spoke, I learned how the colors of the Freedom Bridge hold more significance than I could have guessed on first glance. Nowadays, the blue and yellow contrast across the north-south divide like two friends extending hands, but during the war that same contrast was a running “joke.” According to Vu, anytime the South would paint the southern half of the bridge to differentiate it from the northern side, the North would rush to paint theirs the same color, displaying a resilient defiance to Vietnamese division that would foreshadow the ultimate outcome of the war.

Behind us, a lone flagpole rose high to meet the sun, the Vietnamese flag flapping above our heads. This flag was another target of the Southern forces, who kept blowing it up only to see it quickly rebuilt. Now it stands over the DMZ and its cratered earth, which has been adapted into rectangular shrimp fields by the locals who have returned to claim this once depopulated land.

Figure 4: A note written on a chalkboard in the ruins of a Buddhist school in Quang Tri advertising a school reunion. The Buddhist school was one of the two structures that survived the War.

They have returned to take care of their ancestors, Vu told us. Ancestral worship was introduced to Vietnam by the Chinese, who occupied the area intermittently from 111 BCE until 1427 CE. Nowadays, the practice remains a strong part of Vietnamese spiritual life. In keeping with this tradition, after the war ended many people moved back to the lands where their ancestors had been buried. A member of the families that once lived here, usually the youngest male son, would return to lands marred with bomb-craters and hiding lethal mines because of this strong sense of ancestral lineage.

Here we see how the geography of refuge can be redrawn by the influence of cultural traditions. It’s not that these spaces marked by ancestral significance serve as some form of social refuge (though of course they do) but that they represent a sphere of spiritual refuge within the people’s conscience that counterbalances the instinct to find immediate refuge. It isn’t unlike the nationalism that leads civilians into war, with the understanding that protecting the integrity and power of the nation ensures the survival of their own future, lifestyle, and values—their social refuge.

As a child of a society that has never felt “the sorrow of war,” to quote the Vietnamese author Bảo Ninh, I am unable to grasp the power of such counteracting forces. I look upon the decisions made by these men and women who were forced to be much braver than me, and I can only create a fiction around their humble and heroic decision to return home. Home may have not been where their heart was leading them, but where it lay buried.

Figure 5: Man reenacting the way Viet Cong soldiers would come in and out of the small hidden entrances to the Cu Chi Tunnels

Back in ’54

Bắc 54 was the term used to identify the group of people that migrated south from North Vietnam in 1954 under the Operation Passage to Freedom, a U.S. Navy and French military initiative. Among those who moved south were Catholics, whose religion was now supported by the new president in the South. Christians were a small minority in Vietnam, but that did not stop them from holding power under Diem’s presidency. In Quang Tri, the remains of a concrete church built in 1955 stands as a testament to this power. One of only two buildings made of concrete in the area, it survived (though not unscathed) the ravages of war. The plaque that adorns the otherwise unkempt plot of land around the ruins of this church explains to the visitor that this is “a relic of the war… the memorial of the bravery of our soldiers and people,” not a relic of the Catholic religion or of a small group of people making a home for themselves. This is a small reminder that no meaning is permanent, that the significance of a place or thing is applied, be it through a congregation of people praying or through a round of bullets incrusted into a concrete wall.

In 1954, southerners were also allowed freedom to go north. Many of the soldiers who were in the south during the fighting returned—but not all. Some soldiers remained as sleeper agents in the south, biding their time until the war would inevitably start up again. These sleeper agents are the origins of the Viet Cong, whose stealthy approach to war played a major role in the subsequent North Vietnam victory.

Figure 6: One of the booby-trapped entrances designed by the Viet Cong at the Cu Chi Tunnels

Ideological Home

No Man’s Land. I had never fully questioned the term before I found myself in the Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ. It is a term that carries its poetic meaning right on its branded military-issue sleeve. The mere sound of it is enough to bring up notions of death, inhumanity, and futility. But there is another layer of meaning in the words. No Man’s Land is a land that does not belong to anyone. But it did once belong to someone. Before it was chosen as the space of No Man, it belonged to some man or woman, to a family or community. It was someone’s home, someone’s inheritance, someone’s entire livelihood. So what happened to them?

In the south, the civilians that once populated the fertile lands in the DMZ were shepherded into refugee camps under the Strategic Hamlet Program begun in 1962. Under the leadership of Ngo Dinh Diem, South Vietnam’s first president, the Strategic Hamlet Program was an attempt to thwart communist influence in South Vietnam by separating rural villagers from Viet Cong insurgents and to develop a political population base for Diem’s party. These camps were also meant to provide the inhabitants with a higher standard of living, but this was far from the case. A report from the Pentagon found only 20% of the completed hamlets met the U.S. standard of living. By 1963, after a military coup carried out against President Diem, the program was dismantled.

Though the Strategic Hamlet Program is the best known, it was not the first program within Vietnam that used human displacement for ideological purposes. Others include the 1957 transfer of tens of thousands to uncultivated tracts of land in the center and south of the country or around the Mekong Delta, which was carried out with the intention of eradicating the nomadic lifestyles that still existed in the highlands and of fostering a sense of national solidarity.2 After insurgency mounted in 1958, the government implemented the agroville program, which entailed moving inhabitants from the Mekong Delta into small agrarian hamlets.

Figure 7: Remains of Long Hung Church in Quang Tri. Its concrete structure made it a likely spot of fighting during the war and resilient enough to survive—one of the two structures that did so. It was built in 1955 and remains a remnant of the North ’54 Christians who migrated south.

The hamlets were spaces but can be studied as pieces of architecture. We can analyze the materials, techniques, and structure used in their construction. We can dissect them aesthetically. We can probably learn a lot in doing so. But I would like to study them another way (through a concept that I probably have no right to appropriate): the dialectic.

This is a dangerous little word. In the world of philosophy, the dialectic has had minds spinning in circles since the days of the Ancient Greeks. It is easy enough to explain, but not so easy to employ. Simply put, life is filled with seemingly irreconcilable contradictions. The dialectic method is the attempt to reconcile these differences by putting them in conversation. This conversation can take on many forms, including some that are less dialectical than they are confrontational, but mostly it can have many outcomes, from clean answers, to messy answers, to more questions, to non-answers.

But whatever differences arise, the intention behind the use of the dialectic remains relatively constant. I believe it was the late Marxist philosopher Georg Lukacs who put it best when he wrote that the imperative of the dialectical method is “to change reality.” To change reality we must think through reality. A problem I have with programs such as the Strategic Hamlet has to do with the isolation they engender, with the conversation they eliminate. They are attempts to change reality by force and, whether or not they are successful, the method they employ is dangerous. They take away the dialectic.

In a homestay in Ninh Binh, I sat across from an Israeli who is living proof that people can change their minds (and sorry, but I do mean this in the metaphysical sense). Raised Orthodox, he left the faith and took the mantle of nationalist, settler, and soldier, then left that faith and became a left-wing advocate of Bedouin rights and representation. He spoke to me of his passion for education and his desire to understand indoctrination, dissent, and the loops that the human mind can do around these two poles. His faith in the elastic power of the human mind brought to my mind a thought I had not anticipated. Yes, that elasticity is fascinating, but it also has its limits. In other words, though the mind can jump ship, it does not usually jump into the abyss. It jumps from ship to ship—from ideology to ideology, from belief to belief.

Thinking about these government housing programs, mulling these ideas over, and looking out over the villages scattered across the DMZ, I begin once more to ask myself a question that many reading this will probably already be asking themselves: what does this have to do with architecture? The problem, I realize, is that I cannot give a good answer to that question. Architecture, the way I’ve been taught to understand it, ought to be disengaged from questions of indoctrination and dissent. It ought to be autonomous. Laugier’s Primitive Hut floats easily into the back of my head as I think of all the times architects have been drawn back to their roots, removing style, context, and anything else that may muddy the ideal concept of Architecture.

And yet, I fear the image doesn’t hold the same sway over me as it once did. More and more I find it unbelievable that there are architects who still stand under the banner of an autonomous architecture. To study space is to study its politics, its philosophy, and its history. To study space is to study the bodies that inhabit it, make it, and break it. Studying space as an autonomous entity is like abstracting a political party down to a slogan. It can be done and it is useful, but once it is done it needs to be brought back into conversation with its context.

Figure 8: Entrance to the Vinh Mốc Tunnels

The Underground

In the North, an entirely different approach was used when it came to war refugees. Children and the elderly were moved away from war zones, but all able-bodied men and women were made to remain as a civilian militia meant to help fight the South. These “volunteer” civilians went underground—both metaphorically and literally.

The Vịnh Mốc Tunnels are just one example of the 3.5 kilometers of underground tunnels that the North Vietnamese burrowed beneath and around the DMZ. Used for housing ammunition and people, they were complex networks equipped with booby traps, escape routes, ventilation systems, as well as kindergartens, medical centers, kitchens, and cisterns.

Still above ground and on our way from the car, we passed the hollowed-out trenches that served as a secondary network over the tunnels where children born in the tunnels attended kindergarten, soldiers transported weapons, and farmers went to and from the few fields they were still able to cultivate. I can picture them almost hopefully surviving, separated as they were from the direct fighting. But of course the image in my head is just that—an image.

Figure 9: Naturally hidden ventilation shaft made in the ant hills, using bamboo rods to bring air down to the tunnels.

From 1968 until the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, a small fishing village occupied the second of three levels that still make up the Vịnh Mốc Tunnels. Set against a steep hillside that meets the ocean, these interconnected levels were staggered both vertically and horizontally as a safety measure. The result? A surprisingly strong sea breeze flowed through the dark and narrow passageways. After having crawled and sweated through the Cu Chi Tunnels, I caught myself almost accepting the conditions of those living in the Vịnh Mốc Tunnels. Not too shabby, I heard myself say, finding that I could walk with my head held high. But these words sank to the pit of my stomach as Vu began speaking of the terror that the inhabitants must have felt as the bombs would make the world of clay around them shake.

Vu showed us the couple square meters that a family would have called home: simple holes dug at repeated intervals into the long passageway. He stopped where women would have given birth, a slightly larger hole that opened up into that same long and winding passage. In a segment of the passage that widened no more than three meters to make the sole meeting place in the complex, Vu noted the corrugated walls with shallow enclaves where mats would have been placed—a small kindness. We kept going, always further down. We sidestepped a couple workers making repairs, whose voices we had been hearing since our eyes first began to adjust to the darkness. We poked our heads into the two-level space that served as a bathroom and into others that were used for storage. We kept going, the sea breeze intensifying, blowing salty hope to our bodies so unaccustomed to the claustrophobia we had been denying we had.

When we finally poked our heads out of the shelter, the sea welcomed us with the mellow sprays of its wreaking waves. And I fear that my use of the word “welcome” cannot fully express the impact of the sight after spending just a little while within the tunnels. The fact that these tunnels, unlike so many others across Vietnam, met the sea was no small thing.

Figure 10: View of the beach from the waterfront entrance of the Vinh Mốc Tunnels.

One of my favorite quotes is by the playwright Antonin Artaud, who stated, “It is not opium which makes me work but its absence, and in order for me to feel its absence it must from time to time be present.” Sometimes we can forget the impact that our surroundings can have on us, physically, psychologically, and emotionally, until we experience its lack. As a college student, I spent five years in a campus whose long winter months came with clouds, clouds, and more clouds. But it was only on the lucky days when the sun came out that I would realize how easily those rays could lift my spirits.

Experience—that’s another word that rests at the tip of the tongue of many thinkers, from philosophers to scientists. Its taste is somewhere between palpably real and unreliably false. It’s a word that I have heard architecture professors use with either whimsy or disdain—but not so often with critical application. (I have even heard one professor advise an entire class not to give a second thought to the way people experience architecture). An exception that comes to mind is the late Bonnie MacDougal, whose earnest attempts to get my fellow students and I to understand the world in which we were to help build a new world earned her a permanent space in my conscience. But the experience of space is something designers should neither take for granted nor simplify to the superficial genres of materiality or geometry. Architects should be thinking of the experience of space on the levels of culture, history, or psychology. It may sound extreme, but we should be thinking about it on the level of human survival.

Architects should be constantly questioning and learning about the human experience of the world as it is. From the farmer pulling unexploded mines from their field, to the shoe store security guard sleeping on the job, to the child victim of Agent Orange handcrafting mother of pearl artifacts for tourists—and these are only momentary slivers of the world in Vietnam. Because Bonnie had the right idea. What right do we have to build upon this world if we don’t understand it? The past few months have made the truth in that perfectly clear to me. And my visit to Vietnam has reminded me that I’m not even close to understanding it.

Figure 11: Stairs leading up from the waterfront tunnel entrance up to the other entrances of the Vinh Mốc Tunnels.

2 Catton, P. (1999). “Counter-Insurgency and Nation Building: The Strategic Hamlet Programme in South Vietnam, 1961-1963.” The International History Review 21 (4): 918-940. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40109167.