-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

2019 Edilia and François-Auguste de Montêquin Junior Scholar Fellowship Report (Meyer)

Jan 8, 2020

by

Anthony Meyer, PhD Candidate, UCLA

Dates: August & September 2019

Locations: Mexico City, Mexico

When Europeans ferried themselves across the Atlantic and began to invade Nahua lands in the central Valley of Mexico in 1519, they were instantly drawn to indigenous beliefs and religious displays. Details of expansive temples, sprawling cities, and gruesomely crafted sacred figures took center stage in early Iberian writings of the Mexica (Aztec) world, but while they gawked at strange rituals and visually intricate art and architecture, they failed to grasp the complexity of Nahua religion and its central agents, the tlamacazque. In open spaces and finely made buildings, Nahua religious specialists, known as tlamacazque, or “the givers of things,” were responsible for counseling rulers, protecting sacred forces, bringing ritual objects to life, and shaping ceremonial spaces. Scholars have since mined colonial texts and images to piece together a more accurate representation of Nahua religion, but an overreliance on texts has shadowed the pivotal roles religious leaders had in the Mexica and early transatlantic worlds. Looking instead to art and architecture as critical windows into the lives of these vital leaders, my dissertation examines how tlamacazque amassed and shaped imperial power across sweeping landscapes under Mexica rule and in the early years of Iberian occupation. In particular, my project investigates the everyday and extraordinary dynamics of the tlamacazque world by studying their religious school called the calmecac and open-air platforms where they dazzled spectators with state-mandated rituals.

Contrary to the promoted tale that religious specialists met their demise at the hands of European invaders, they continued to be of critical influence, not only in maintaining traditions but also in safeguarding sacred spaces and objects. Europeans incorporated Mexica religious spaces in surprisingly diverse ways, belying the simplified narrative we are taught in survey courses: that Iberians razed temples and surmounted them with sixteenth-century Christian churches. In fact, sixteenth-century material culture, as Alessandra Russo has noted, provides us with unique glimpses into the ways that Nahua peoples had “to metaphorically rethink space and time.”1 With the generous support of the Edilia and François-Auguste de Montêquin Junior Scholar Fellowship, I was able to closely examine these changes and reconfigurations for six weeks in two important Nahua urban areas—Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco—located in present-day Mexico City. These architectural studies helped me to understand the diverse approaches Europeans took when trying to eliminate Mexica sacred spaces, as well as how Nahua religious specialists possibly restored meaning to these entangling and transforming places.

When I wasn’t toiling with the scratchy penmanship of sixteenth-century manuscripts at the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City, I was spending time at nationally preserved archaeological sites. The first urban space I investigated was Tenochtitlan, the once grand imperial and ceremonial capital of the Mexica empire. Archaeologists have been working hard to unveil the ceremonial precinct which still lays partially buried beneath bustling downtown Mexico City. Excavated from 2006 to 2008, the calmecac at Tenochtitlan provides us with a critical glimpse into the everyday lives of religious leaders and their students.

Figure 1 – View of excavated calmecac from the ceremonial precinct of Tenochtitlan, showing an open-courtyard likely used for instruction. There are two construction phases exhibited, dating to the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century. Photograph by author.

Composed of open-air courtyards, closed dormitories, and communal living spaces, the calmecac served as both a training center and house for teachers and their pupils. These Mexica schools were filled with the chatter of young girls and boys, the smell of incense and fire, as well as songs and dance accompanied by the booming, whistling, and tinkling of drums, flutes, and rattles. Each city-state had a calmecac to train its noble youth in religion, philosophy, politics, and art making to become future elite rulers and tlamacazque. We even get a sense of how these spaces were used by the preserved footprint of either a teacher or pupil in the architectural fabric.

Figure 2 – Footprint in lime plaster at the Tenochtitlan calmecac. Photograph by author.

Part of my project this summer was to survey and map the spatial layout of the calmecac. One of the major questions I had before traveling to Mexico was how the design of the calmecac complex influenced early Christian teaching spaces, and the answer is probably quite a bit! The sixteenth-century mission complexes of New Spain also utilized a variety of open-air teaching spaces and dormitories, architecture that’s unique to the Americas, and the relationship this form has to the spatial design and use of Mexica calmecacs is uncanny, an insight I will now investigate further in my dissertation.

Tenochtitlan also housed a suite of temples and platforms used for both daily and festival use. After the Iberian invasion, the precinct and its architecture changed, providing the foundations for early colonial structures, including residences, water sources, and a series of construction phases for the main cathedral. Previous scholarship on sixteenth century New Spain has focused on colonial buildings and spaces associated with indigenous rulers, but my project for the de Montêquin fellowship expanded these studies by dealing more with tlamacazque-related spaces.2 In particular, I was able to analyze indigenous materials and forms used to construct the first buildings in the precinct behind the central Mexica temple.

Figure 3 – Evidence of indigenous construction during the colonial period at the ceremonial precinct of Tenochtitlan. A combination of lime plaster, wooden poles, and tezontle (pumice) infill made these structures highly resistant to earthquakes. Photograph by author.

Nahua building techniques such as wooden poles and plaster mounds gave colonial structures stability and form, and many were likely placed there with the aid of tlamacazque hands. One of these early structures was an abandoned Franciscan monastery, deemed unsuitable and relocated farther away from the precinct. However, the Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo remained in the area right near the former calmecac, suggesting a much more complicated history of early colonial building. Here, didactic spaces were allowed to graft onto former models while religious ones like the Cathedral and Franciscan monastery were divorced from their temple antecedents. During the summer, I was able to uncover these spatial relationships and reuses, as well as articulate possible Iberian motives for doing so.

The remainder of my research outdoors was spent at Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan’s sister-city to the north, which offered another example of architectural entanglement in its sacred precinct. Instead of completely razing the site, Iberians placed a new Christian complex as a backdrop to the central indigenous temple, directly beside the former calmecac. Next door, the Colegio de Santa Cruz, a school first designed to indoctrinate indigenous priests (though this never came to fruition), was annexed in a similar spatial arrangement as the Mexica’s pairing of central temples and religious schools. Archaeologist Guilliem Arroyo has spent decades excavating various portions of the site and its colonial structures, and I investigated these spaces to build on his research.

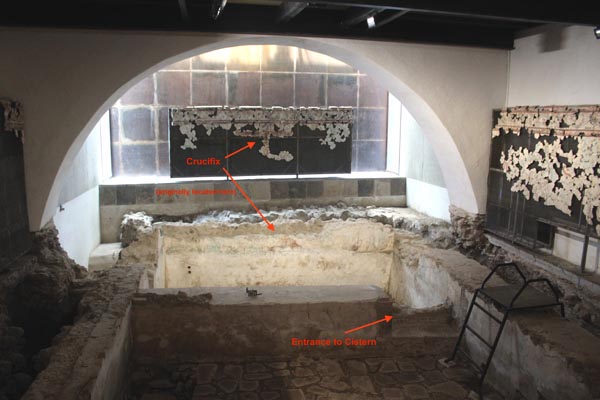

Part of my project at Tlatelolco was to gain access to the Caja de Agua, a sixteenth-century colonial cistern with Mexica-style murals that would have been available to indigenous converts at the Colegio. On the morning of September 2, I was greeted by an INAH official at the site who opened the doors of the Caja (you can only gain access by appointment due to preservation issues), and he spent time guiding me through the space and its visuals. Used as the primary water source for the colonial church and school in the first decades of Iberian occupation, its walls are marked with elaborate details that show Nahua artists attempting to understand Christian concepts; e.g. nine stones underneath the crucifix to represent the nine layers of the Nahua underworld, fishermen in indigenous canoes, and the toponym for Tlatelolco located near an image of an eagle and a jaguar. One of the most intriguing aspects of this space was its use: as Nahua peoples entered the cistern to collect water, they had to bend and genuflect in front of the crucifix on the back mural. The Caja, then, exemplifies a spatial strategy on behalf of European friars to convert indigenous members through embodied, habitual action, but at the same time, indigenous motifs on its walls demonstrate ways that Nahua peoples converted on their own terms. Although I found no conclusive relationship in the archives, we can speculate what it would have been like for the religious leaders who continued to reside in Tlatelolco and draw water from this visually rich well.

Figure 4 – Mural segment depicting a fisherman in an indigenous canoe. Caja de Agua, Tlatelolco. After 1536.

Figure 5 – Visitors to the well would enter and stoop low to collect water from the shallow depths, genuflecting in front of the looming crucifix at center. The upper parts of the murals have been separated for conservation purposes. Caja de Agua, Tlatelolco. After 1536. Photograph by author.

One of the other fascinating aspects of studying Tlatelolco and its sixteenth-century colonial construction is the evidence of stone reuse at the Iglesia de Santiago. Many of the later phases of Mexica buildings in both Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco formed the scaffolding of emerging colonial cities. At Tlatelolco, that shift is legible on its exterior walls, with many builders’ stones once used in earlier Mexica constructions now marking the church’s external layers.

Figure 6 – Frontal view of the Iglesia de Santiago Tlatelolco. Photograph by author.

Figure 7 – A marked builder’s stone likely reused from one of the Mexica religious buildings surrounding the sixteenth-century church complex. Photograph by author.

The practice of marking buildings must have continued given the presence of a Mexica-style building stone on the church that depicts a rabbit-like creature surrounded by European ornament. The Iglesia de Santiago would have been constructed by Nahua builders, so it is unsurprising we find innovative ways that indigenous makers continued their practices of marking buildings in the sixteenth century. During the summer, I was able to note where these stones are located, record the materials used, and piece together construction strategies that overlapped with Mexica traditions.

Figure 8 – A marked builder’s stone showing a rabbit with ornamental scroll motifs. Photograph by author.

Having the chance to investigate these spaces while financially supported by the Society for Architectural Historians through a de Montêquin fellowship has pushed my research in exciting directions. It allowed me to connect archival findings of tlamacazque presence in colonial spaces with the actual architecture itself, provoking me to consider how these striking religious leaders experienced new changes within the precincts they had inhabited for their entire lives. Moreover, it has enabled me to make a rich contribution to the field by complicating the simplified narratives that have been unquestioned in studies on the first decades of Iberian occupation in central New Spain. Much more work remains to be done on this volatile and precarious sixteenth-century moment, but thanks to instrumental funding sources like the Edilia and François de Montêquin Junior Scholar Fellowship, we have much to look forward to as we disentangle the artistic and architectural practices that cluster around the ethnically and religiously diverse actors of this period.

1 Alessandra Russo, “Plumes of Sacrifice: Transformations in Sixteenth-Century Mexican Feather Art.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 42 (Autumn 2002): 244.

2 For example, see: Barbara E. Mundy, The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2015).